Inspection of Operational Assurance in the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service

Related Downloads

Post-incident OA arrangements

131. The Service arrangements for post-incident OA are contained within the GIN – Operational and Event Debriefing(30). The GIN details that: ‘Effective debriefing plays an important part in maintaining and improving standards across the Service. Debriefing also plays a vital role in supporting a learning culture necessary to promote a safe and effective workforce… Debriefs are an essential and robust evaluation technique, used to identify significant factors giving rise to shortcomings or achievements. By debriefing, the SFRS can review, evaluate and amend policies, practices and procedures appropriately’. The two main components of the process are ‘hot debriefing’ and ‘structured debriefing’.

132. A hot debrief is the informal method of reviewing activity and sharing learning immediately after an incident, preferably at the scene and, where possible, involving all personnel. Partner agencies, such as Police, Ambulance and other organisations involved, can also be included in the hot debrief to provide their perspective on the resolution of the incident. This can help to promote collaborative multi-agency working. The Service considers hot debriefing as mandatory for all incidents, irrespective of whether a structured debrief process is expected to take place thereafter. When hot debriefing an incident, the IC or debrief lead are required to make notes of discussion points for future reference and to inform a subsequent structured debrief, if required. If there is ORL it is captured electronically on an OA13 debrief report form on OARRS.

133. A structured debrief is a documented and auditable procedure for obtaining, collating and reviewing information about incidents, for the purposes of continuous improvement. Wherever possible, a structured debrief is expected to be conducted as soon as is reasonably practicable after the event. Ideally, the Service expects that this should be within 28 days, to ensure learning points are still fresh in the minds of those involved in the incident. To adequately prepare for a structured debrief, all relevant information should be collated to enable an understanding of the sequence of actions from start to finish of the incident. To streamline the debrief process, individual OA13 debriefs may be issued electronically and automatically collated on OARRS, thus reducing the logistical challenge of trying to bring large numbers of personnel together at the same location.

134. Non-operational events, such as those impacting on SFRS ‘business as usual,’ e.g. power outages, severe weather, ICT-related issues and Pandemic Flu, may be subject to a debrief process where ORL is apparent. In addition, local or regional event debriefs can be carried out by staff, where applicable, following the principles set out in the debrief processes and utilising the OA13 report on the OARRS for recording the debrief outcomes.

135. A key component of any process is the ability to progress identified learning points raised through the debrief process and ensure they are actioned with subsequent improvement made. To support a learning culture, it is vitally important that individuals can raise learning points, have a process for them to be progressed, and to receive feedback as to whether the points raised have been actioned or otherwise. It is the responsibility of all managers to ensure that any learning that can be addressed locally is actioned at the earliest opportunity.

136. Where learning is addressed locally, it should be recorded on the OA13 form, to close off the learning identified. Where learning cannot be addressed locally, it should be passed to the next level of authority for progression and/or decision. This is recorded on the OA13 form and includes the proposed route for progression, i.e. submit to the regional SAIGs for progression etc. Wherever possible, OAD should feedback to the submitting IC or debrief lead on the progression of items that have been submitted and accepted for progression.

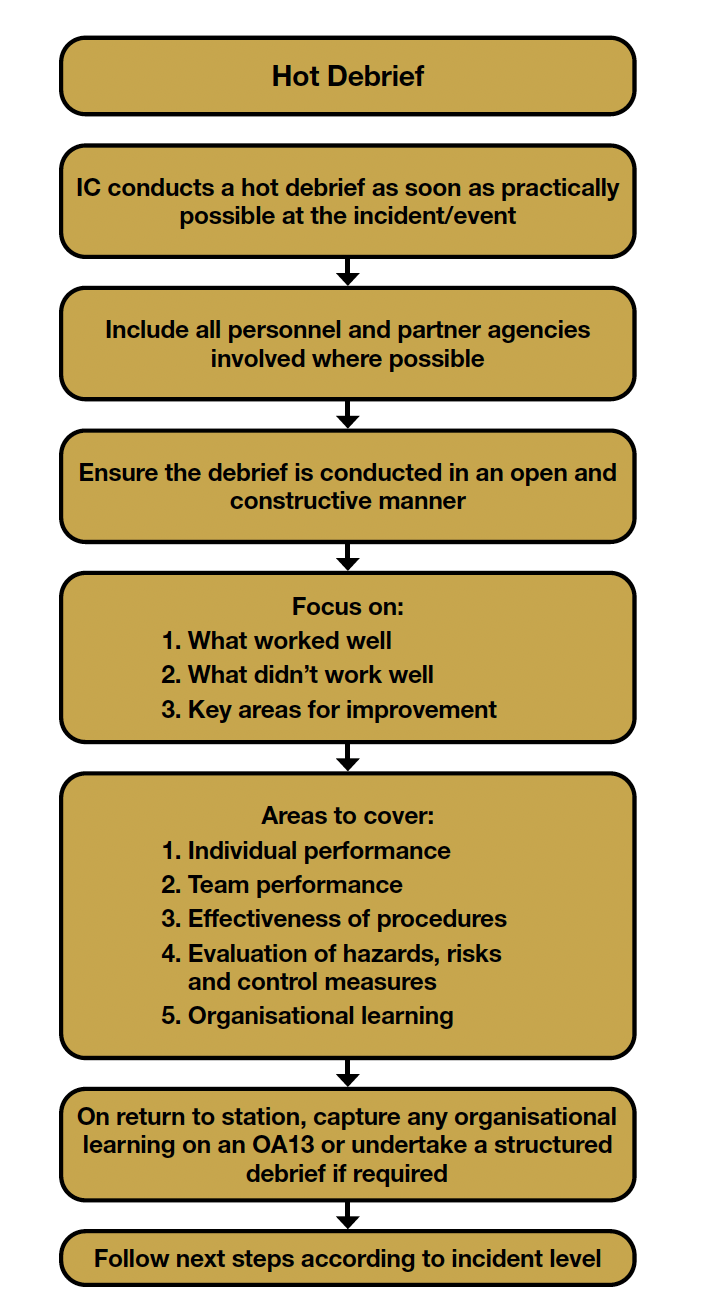

Hot Debriefing

137. Staff were very conversant with the hot debrief process and provided a lot of good evidence surrounding the positive use and learning from this form of debrief being conducted at incidents. We found that the process in Figure 3 was generally followed well and there was an expectation that a hot debrief would be completed at any operational incident of note. In most instances, staff used the hot debrief immediately after an incident but there was a level of pragmatism regarding its application depending on the type of incident, weather conditions, welfare consideration, exposure to contaminants, ongoing incident ground risk etc. In such instances staff were more than comfortable conducting the debrief back at a workplace when it was more appropriate.  Figure 3 - Hot Debrief process

Figure 3 - Hot Debrief process

138. Staff also reported the increased use of the hot debrief for checking post-incident Mental Health and Wellbeing (MHW) and initiation of the PISP. This evolution of the process was considered an extremely positive practice.

Good Practice 7

We found examples of the changing culture to include PISP and MHW within the Hot Debriefs to be incredibly positive and that this good practice should be used to influence future IC development.

139. An aspect of the hot debrief process was that it tended to result in somewhat localised learning. Staff were very proactive in discussing learning within their own watch or crew, however, this normally remained consigned within that team with informal transfer of learning between WCs on station only happening occasionally. Formal learning transfer at station management meetings appeared to be limited, due in part to there being inconsistent examples of management meetings and reluctance to ‘air dirty linen’, but also with occasional examples of good practice and innovative use of digital systems. There was limited evidence of regional transfer and rare examples of transfer of learning within the whole SDA or Service-wide. We found that many of the local meeting fora and agendas were focussed predominantly on management performance issues and that operational performance and assurance did not feature highly or equitably. It was concerning that local OL did not seem to be routinely communicated in a structured fashion or to be part of station culture.

Area for Consideration 11

The Service should consider reviewing how local OL is informally transferred within its management structures and reinvigorate the need to ensure that learning is reported appropriately.

140. Many managers reported that the value of hot debriefs diminished in direct relation to the size, scale and protracted nature of the incident. This was because crew turnover at larger incidents meant that debriefing the initial stages of the incident and original crews in attendance was very unlikely. In addition, staff felt that it was also unlikely that the attending crews and IC teams’ changeover would be exactly aligned, so the opportunity to debrief that phase of the incident could be problematic. As such, conducting a hot debrief was sometimes viewed as being ‘belts and braces’ as opposed to adding value.

141. We found reference to hot debriefing in many of the OA documents and within the ICL and TFoC processes but no direct reference to acquisition training for managers. Reference to debrief training within the Road Traffic Collision Instructor and Breathing Apparatus Instructor courses was also cited, however, staff reported that access to these courses could be limited and could therefore not be relied upon as routine training. The structure and standard of hot debriefs was generally not formally taught, and learning and development was based mainly on experience and observation of other ICs. Staff generally found the standard of hot debriefs to be constructive and positive but felt that the success of many depended on the experience, leadership style and personality of the conducting IC and any historic observation. Many managers felt that they had not been properly prepared to conduct hot debriefs to a standard expected by the Service.

Structured Debriefing

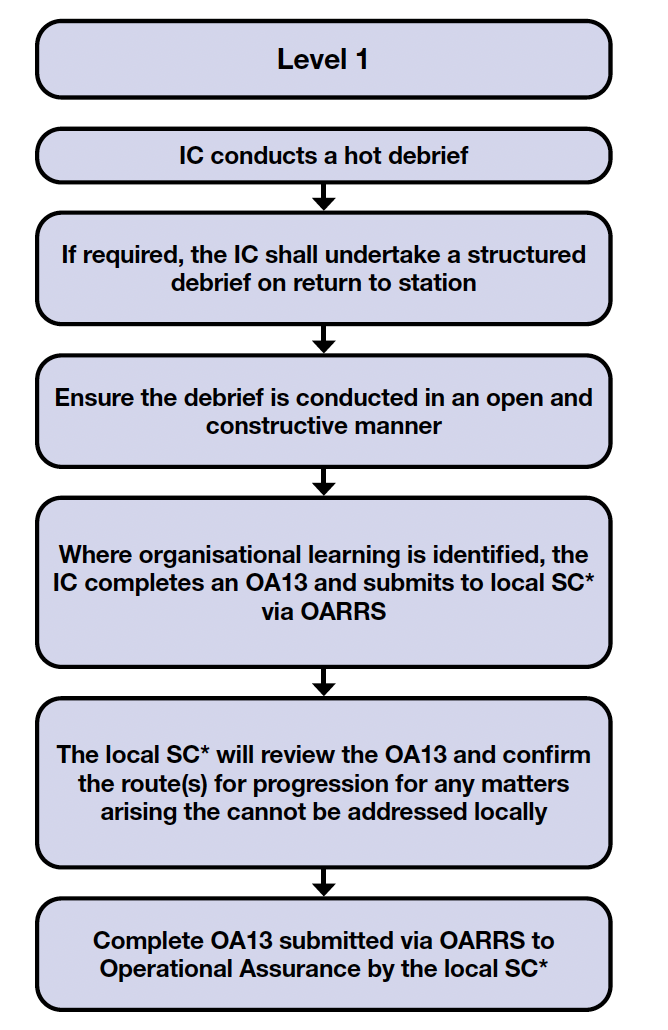

142. On conclusion of a L1 incident, the IC is required to conduct a hot debrief and, if appropriate, should then undertake a structured debrief on return to station (Figure 4). If a structured debrief is required, the IC should consider the inclusion of all other parties involved, i.e. OC, Police, Ambulance, etc. Where OL is identified that cannot be addressed at a local level, the IC should complete an OA13 on OARRS and submit the debrief report to the respective local SC responsible for the station area where the incident occurred. The reason for submitting the OA13 to the respective local SC is to ensure that local matters arising are addressed promptly, e.g. lack of Operational Intelligence (OI), multi-agency issues, poor water supplies, etc.

*The local SC is the SC responsible for the station area where the incident occurred.

Figure 4 - Level 1 debrief process

143. We reported in our WSDA inspection that in relation to OA, staff were routinely frustrated that the Service did not seem to be learning from certain types of incidents and that there was, in their opinion, gaps in operational preparedness. Specifically, we recorded that ‘given the rise in forced entry incidents, bespoke equipment to assist this type of incident such as a power drill, reciprocating saw and door opener had not been provided, after repeated requests’. Whilst speaking to staff, during this inspection, our understanding of this issue was further reinforced. We found similar types of incidents to be those involving assistance to Scottish Ambulance Service with bariatric patients, large animal incidents, electric vehicles and solar panels. Frustrations surrounded limited training, equipment and procedures for these incident types, that staff believed could be anticipated and foreseeable. Many of these incidents form day to day operational work and are not new to the organisation. It is therefore important to attempt to understand why there is an apparent disconnect between the perceived, expected and actual operational preparedness.

144. It is apparent that many of these incident types detailed above would normally be categorised as L1A – L1D within the ICS. As such, there is no automatic requirement within the guidance to carry out a structured debrief or complete a OA13 to formalise learning. For this level of incident, we found that staff overwhelmingly use hot debriefing as the means of learning with awareness of the need or ability to use the OA13 formal report limited. To resolve issues for this type of incident many staff believed the correct action was to report concerns informally to their line management, with the expectation that they would escalate these up through the Service structure. Most reported that this approach seldom resulted in a satisfactory resolution, and just increased frustration and disengagement.

145. We surmised that this expectation may be over ambitious, given the hierarchical nature of the organisational governance and structure of the SFRS linked to the Service-wide nature of some of the issues. As such, there may be a high degree of under-reporting for smaller incident types, and therefore potentially no body of evidence being developed to initiate sustained actions for improvement at the correct level or place within the organisation. This issue is probably exacerbated by the functionality and data analysis limitations of OARRS. Given that L1 incidents form the bulk of incidents and the potential challenges with analysis and reporting, there is a concern that the Service is not effectively and efficiently learning from its high-frequency operational activity.

Recommendation 6

We recommend that the Service review how it gathers debrief information from L1 incidents and analyses this, to ensure that ORL encompasses issues generated from all incident types.

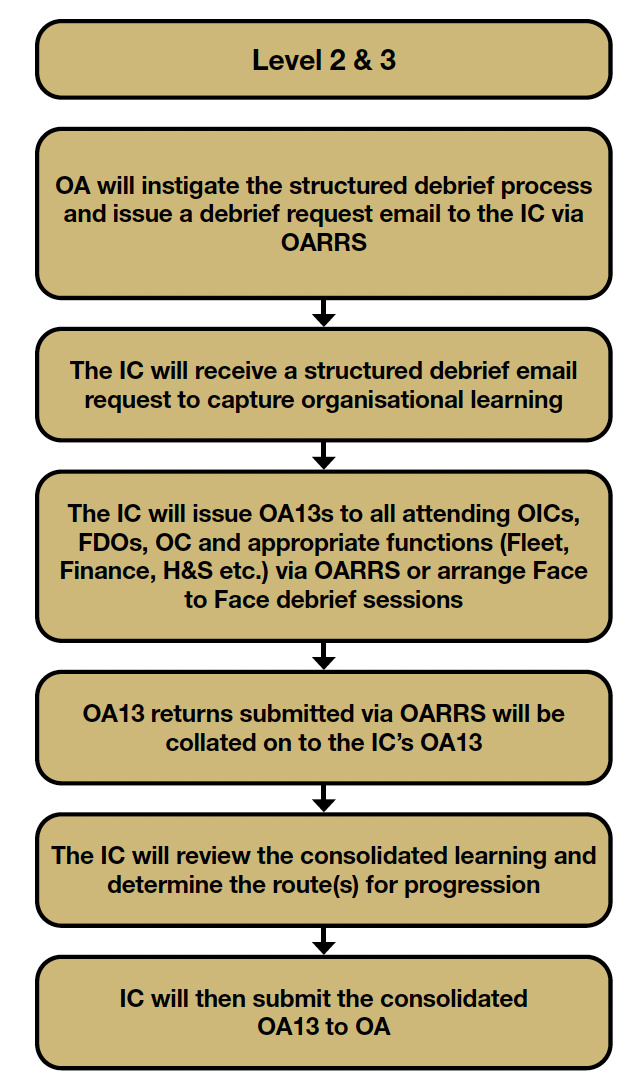

146. Following a L2 or L3 incident, OAD will issue an email via OARRS to the most senior IC who attended over the duration of the incident, informing them that a structured debrief is required and that they are the nominated debrief lead (Figure 5). It is then the responsibility of the IC to undertake the debrief. The IC may choose to conduct the debrief by issuing an OA13 via OARRS to all attending appliance OiCs, FDOs, OC, etc., organising a face-to-face group debrief or by utilising video conference (VC), telephone, etc. Where the IC chooses to issue OA13s via OARRS, all the OA13 returns are automatically collated on to a single OA13 debrief report for the IC on OARRS. Wherever possible, ICs address any local matters arising.

Figure 5 - Level 2 and 3 debrief process

147. The OA Policy allows commanders to opt for a face-to-face/VC process or to issue an electronic OA13 information gathering process on the OARRS as detailed previously. Both systems have their merits as face to face allows for positive human interaction and the opportunity to verbalise and contextualise issues, whilst the OA13 process is automated and much more efficient when managerial capacity is limited. As such, there is an expectation that both may be used in a blended approach to ensure good ORL.

148. We found convincing evidence that the electronic consolidated OA13 process was being utilised and limited evidence that face-to-face/VC debriefs are used routinely. Where we did observe, or were provided evidence of, face-to-face/VC structured debriefs, these had normally been supported and/or facilitated by the OAD and were incredibly positive experiences for those involved. In our WSDA inspection, we found limited evidence of managers conducting face-to-face/VC debriefs and almost universally, the standard approach was to use the consolidated OA13 electronic system. Our fieldwork for this inspection confirmed this to be the case throughout the Service.

149. In themselves, the consolidated OA13 forms are not the issue as they capture all the necessary feedback in an efficient automated manner. The issue with this aspect of the process is the fact that the consolidated form is being accepted as a structured debrief of the incident, rather than it being just a consolidated list of feedback. Staff confirmed that the consolidated lists are rarely discussed with those that submitted them and as such, issues are not filtered, clarified, learned from or given context as they would normally be in a face-to-face/VC process. Therefore, consolidated OA13s are being submitted into OARRS where the previously documented limitations on functionality, OAD capacity and manual nature of analysis find the identification of ORL challenging.

150. It is not clear why there is a prevalence of using the consolidated OA13 process. In our WSDA report we detailed that some reasons may be the convenience of the electronic system, the capacity needed to conduct a face-to-face/VC process and a lack of development and resulting confidence in debrief skills. Throughout our inspection, we observed that these reasons were still valid, as well as issues regarding the limitations of support provided by the OAD, coupled with limited training and awareness of the OA system.

Area for Consideration 12

The Service should review the OA13 process to ensure that effective and appropriate debriefing of consolidated OA13 is being conducted.

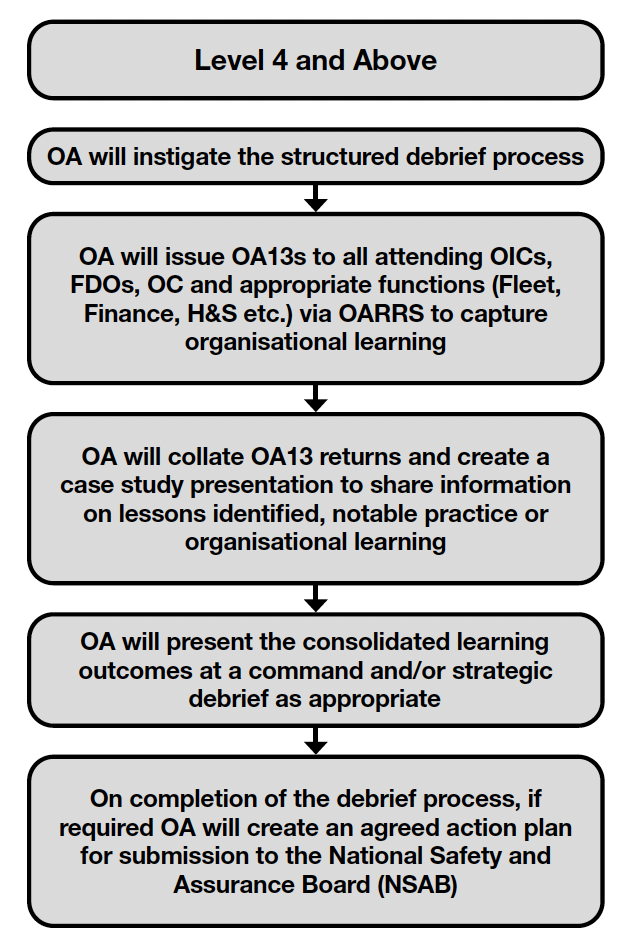

151. The Service details that all L4+ incidents require a formal structured debrief process and that they shall be coordinated and managed by the OAD (Figure 6). On conclusion of a L4+ incident, OAD issue an OA13 via OARRS to all attending OiCs, FDOs, OCs and appropriate support functions, where applicable (e.g. Fleet and Equipment Workshops, Finance, etc.). OAD also arrange for debrief submissions from partner agencies if applicable. OAD collate all OA13 returns, consolidate the learning and create a case study (CS) presentation to share information on the positive aspects, the challenging aspects and action(s) that have been taken or are required to be taken to improve performance. If required, the key aspects are presented at a strategic debrief, and shared throughout the Service at a later time via a CS presentation, FLU, or UI etc.

Figure 6 - Level 4+ debrief process

152. We found evidence that the Service is conducting structured incident debriefs for L4+ incidents which were facilitated by OAD. These were generally very memorable to staff and included recent examples such as, Breadalbane Street in Edinburgh, Katherine Street in Livingston and High Camilty in West Lothian. Due to the scale, and therefore infrequency of these types of incidents, there were limited instances recounted by staff of being involved. In addition to these debriefs, we also found that the OAD had facilitated structured debriefs recently for other significant events and lower-level incidents such as Cannich Moor in Highland, New County Hotel in Perth, Linwood Recycling Centre in Renfrewshire, MV Ultra Virtue in CoG and Storm Babet. The Governance system was utilised to manage all these processes, ultimately ending at the TSAB in an action plan for completion.

153. It is clear that the Service is very sensitised to learning from high-impact, low-frequency incidents and has good process in place to capture this Service-wide learning. Consequently, the majority of the OLG workload derives from these types of debriefs. Staff who had been involved in these debriefs were very complimentary of the processes and overall found it a good engagement process. Negative feedback generally centred around the bureaucracy involved in making change, silo working, the lack of personal feedback, the timescale for learning outputs to be published and the unclear link to improved outcomes.

154. HMFSI had the opportunity to observe an L3 facilitated debrief, via a VC meeting, and found the process to be very constructive, engaging and a positive forum for potential learning and development. It occurred to us that as an observer, the occasion for learning could be very profound and that the Service may be missing an opportunity by not allowing general observation as a development tool. It is understood that there would need to be controls to this, however, these issues would not seem insurmountable and in our opinion the potential benefits would far outweigh any downside.

Area for Consideration 13

The Service should consider expanding the audience of structured debriefs and allow observation as a tool for learning and development.

155. There was robust evidence of ICs submitting a completed OA13 form when requested and we were convinced of routine normalised use. The Service provided partial data for completed OA13 forms for the period of 2018 to 2023 which indicated that this process is being completed to a degree. However, it was unable to provide completion rate data for the same period, or evidence to support the ongoing use of OA13 information for debriefing, and/or trend analysis toward ORL. In addition, it could not provide statistical information as to the number of L1 to L3 incidents that had been debriefed independently by the attending IC.

156. As detailed, the trigger for structured debriefs within the Service is predominantly derived from the incident levels. The Service also has the flexibility to be able to debrief any incident and has done so in the past. The incident level system is very much a blanket approach, and due to the restrictions in monitoring and analysis detailed previously, there is potential to miss learning opportunities at smaller incidents. The C&C benchmark process detailed the NFCC NOL triggers, which are more aligned to specific incident types and events and provide potential additions or alternatives for consideration. As such, the OAD has undertaken to review these triggers throughout 2025 with a view to making recommendation for improvement thereafter. We believe that this review would be appropriate and may identify opportunity for improvement.

Area for Consideration 14

The Service should consider reviewing the current debrief triggers as recommended within the benchmark process to identify if improvements can be made.

157. We found that the concept of hot debriefing within OC was well understood and instances of practising it were reported. However, staff were acutely aware that the working environment within OC was slightly different, in that they would normally be dealing with numerous incidents at one time, whilst incident command attendance was normally singular. As such, staff accepted that the opportunity to debrief an incident could routinely be inhibited by other ongoing workload, and that a pragmatic approach was required. This understanding and pragmatism normally led staff to debriefing incidents more structurally when time, capacity and workload allowed, which seemed to produce more tangible learning for OC.

158. As detailed previously OC are a vital component within OA and as such are included within the ethos of the OA Policy. The nature of the role within the Service, whilst operational, does not normally include attendance on the incident ground and, many of the aspect of the Post-incident GIN do not apply. However, their role within the operational cycle, out with attendance on the incident ground, is just as, if not, more important. Consequently, there is a requirement that they complete a structured OA13 form as and when requested. Like the OA06, many of the cells within the existing OA13 form are specific to incident ground attendance and do not apply directly to OC operational procedure or systems. Similar to the OA06, we were pleased to note that OC have developed their own version of the OA13 form (OA13OC) in order that they can formally capture learning specific to OC procedures. It is also understood that this form is not accommodated within the OARRS, and the input and output is administered by the OC management team.

Good Practice 8

The development of the OC-specific forms was pleasing to observe and staff should be commended for the innovation.

159. OC provided instances of contributing to structured debriefs utilising the OA system as well as being involved in face-to-face/VC debriefs for larger incidents. They also noted that they routinely completed the OA13OC form, which captured specific and bespoke learning for the OC. Staff reported that the perception seemed to be that historically OC were overlooked from many of the formal debrief processes and that this was indicative of their pervasive feeling of being an afterthought. In support of this, we are aware that the C&C benchmark process highlighted potential gaps in their attendance at debriefs, which had now been remedied. This was supported by OC staff reporting inclusion in a number of recent prominent level debrief processes. However, it is disappointing to note that OC and their part in operations is not considered within the holistic OA systems, and as such ORL may be less efficient and effective.

Area for Consideration 15

The Service should consider how integrated OC is within the current OA processes and ensure that they are fully involved in the development and review of future ‘post-incident’ process change.

Training and Exercising

160. The operational event and debriefing GIN details it is designed to support the debriefing of operational incidents, training events and exercises. In this instance and putting operational incidents aside we understand that simply, training is the acquisition and maintenance of skills and knowledge, whilst exercising is the testing of the skills and knowledge. Debriefing operational incidents and significant events is a reactive process born from the need to learn from how the Service has responded.

161. However, debriefing training and exercising would seem to be a proactive process born from the need to learn from how the Service is designed to respond to known incident types. In essence, training and exercising will stress test the equipment, procedures and training prior to attending incidents and is equally, if not more, important to the reactive process, as it may identify learning opportunity before a problem occurs. It is understood that the Service has a statutory ‘near miss’ H&S reporting process, which may act as a proactive circuit breaker for learning. This system is imperfect, however, as it is prone to documented under-reporting.

162. We found almost no evidence of training being debriefed in a format that would formally assist in OA. We were provided with limited examples of large-scale and multi-agency exercises being debriefed, and where this did happen positive learning outputs were developed. However, in general we found limited evidence that internal exercising was being debriefed, with most staff openly reporting that exercising was not something they would consider formally debriefing for OA.

163. Staff were unable to explain why exercising was not routinely debriefed, as there was general acknowledgement that learning prior to an operational incident would be more effective and safer. Issues such as, unclear policy and process, limited management learning and development, limited communication and engagement, unclear values etc. were all potential reasons provided. The requirement to debrief training and exercising is part of the ‘post-incident’ process, that staff routinely connected with operational incident attendance and may also be a reason why it is overlooked. We observed that training and exercising debriefing may therefore be better aligned to the ‘pre-incident’ process which is more associated to securing operational preparedness prior to attending incidents.

Recommendation 7

We recommend that the Service review how and when it debriefs training and exercising to ensure that there is suitable proactive learning to enhance ORL outcomes.

Operational Discretion

164. The Incident Command Policy and Operational Guidance (ICPOG)(31) details that most incidents will be brought to a safe and successful conclusion by the formulation of a tactical plan based on a framework of relevant SOPs, incident risk assessment and OI available. It is recognised that it is impossible to anticipate every incident which may occur and provide a SOP for every situation. In circumstances where the relevant SOPs do not provide adequate guidance to formulate an effective tactical plan, the IC should consider exercising professional judgement to adapt procedures, this process is termed OD. It is emphasised by the Service that OD is not an instruction for personnel to routinely deviate from SOPs. The purpose of OD is to provide ICs with guidance to make calculated risk-based decisions when faced with unforeseen circumstances. Tactical outcomes that may justify OD include:

a. saving human life;

b. taking decisive action to prevent an incident escalating; and

c. incidents where crews taking no action may lead others to put themselves in danger.

165. OD should only be applied when the benefit of taking action outweighs the inherent risk to achieve the objectives of the tactical plan. In all cases, the IC should be able to explain and justify the rationale behind the decision to apply OD. The IC’s decision-making process should not be judged on the outcome of the incident but on the decision-making rationale. The Service states that ICs will receive their full support in all instances where it can be demonstrated that decisions were assessed and managed reasonably in the circumstances existing at the time and taken in compliance with this policy. The ICPOG states that ‘all instances where OD is applied will be subject to review under the operational assurance policy to ensure the Service is able to learn from the experience’.

166. We were provided evidence that the declaration of OD is a relatively uncommon event, and when used there is an investigation process conducted by the OAD. The reported output of these investigations often concluded the misapplication of the OD process, the reasonably foreseeable nature of incidents, and the subsequent need for further personal development. However, there were occasions where the need for ORL was identified and subsequent recommendations for change made from this process, which was an important aspect.

OA21 Process

167. The post OA process is supplemented by a GIN titled OA21 – 21 Day Investigation Procedure(32). The aim of this procedure is to ‘provide interim recommendations to the National Safety and Assurance Board (NSAB) within 21 days of the activation of the OA21 process for any relevant health and safety event, whilst the full investigation process is ongoing’. The OA21 investigation procedure captures short-term risk-critical recommendations that require specific actions or interventions to prevent reoccurrence of the safety event under investigation. Due to the nature of the OA21 investigation process and the limited time available to capture all presentable evidence, there may be circumstances when the outcomes from the OA21 investigation are superseded by the findings from a full investigation. The 21-day turnaround period is aimed at mitigation of risk as well as reoccurrence of H&S events and is also believed to be reflective of industry best practice. The instigation of the OA21 procedure shall not delay the commencement of a full H&S investigation.

168. The OA21 procedure may be activated in the following circumstances:

a. reaction to H&S events that require a significant level of investigation;

b. a near miss event with the potential to cause significant injury;

c. an injury to SFRS personnel that results in hospital treatment;

d. significant safety events involving other FRS both nationally and internationally; and

e. any incident / event of interest to the TSAB.

169. Staff reported that this process was generally considered to be positive and allowed for a quick identification of safety improvements. However, there was a perception that the process may have become obsolete and consequently concern that it had not been used for recent significant and high-profile safety events within the Service. We found that between the five-year period of 2019 to 2024 the process was used eight times for incidents of varying nature, size and scale. The trend across the reporting period was that there was less use of the system recently, which may account for some comments. The decreased use may be due to many differing factors, however, there was no conclusive evidence to point at a decision not to use it. The Service provided assurance that the process is active but that it is being reviewed and developed into an amalgamated SA process, being renamed SA21. The Service also detailed other investigative processes that had been used for recent significant incidents due to their nature and risk to the organisation.