Inspection of Operational Assurance in the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service

Related Downloads

Outcomes

170. The OA Policy details ‘the outcomes from the OA process support the continual review of SFRS policy & procedure, training standards and assets & equipment with a focus to continually improve firefighter safety’. Of particular note, outcomes such as CI, culture, communication and engagement featured heavily in our inspection.

Continuous Improvement

171. CI from an operational aspect has three main outcomes, which are reviewed training, policy and equipment. Objective evidence provided in the form of the OLG Tracker, TSAB papers, SA Quarterly and APR, PC and SDC papers, OA reports etc. detailed actions and improvements. Subjective evidence from staff such as awareness of increased PPE stock for decontamination, the introduction of wildfire equipment, the introduction of new digital fireground radios, changes to initial BA training also demonstrated that there was palpable change that staff could recognise as improvement. Consequently, it was easy to observe there are numerous actions being completed that illustrate improvement which directly or indirectly support the three aspirational outcomes.

172. Conversely, it was also apparent from staff feedback there were issues that were a continuous source of frustration and concern that seemed challenging for the Service to resolve. As well as those incident types previously detailed in the structured debrief section there were additional concerns raised around welfare and relief provision at large-scale or protracted incidents, under provision of wildfire PPE, new pumping appliance design and equipment, the implementation of high-rise building evacuation procedure, command support vehicle provision, the standard of hot wear BA training etc. It is understood that the Service has uniformed staff within the research and development department and also has engagement fora such as a User Intelligence Group (UIG) and the New Appliance Working Group (NAWG) to give staff a voice over and above normal engagement process.

173. However, many of these unresolved issues were reported as being protracted, having been repeatedly reported over many years so it would seem there is a disconnect somewhere within the processes. As detailed previously, the functionality of OARRS makes it difficult to determine whether this subjective feedback from staff aligns to objective debrief data that may be used to compel change. Additionally, staff that reported these issues did not sometimes appreciate that they could be a direct OA matter and as such, some had not contemplated utilising the OA process to highlight them.

174. It can therefore be observed that the Service is making improvement continuously from significant incidents, thematic audits, case studies, NOL and OD outputs, which may have a more acute high impact risk to the organisation due to their nature. However, there remains a question regarding whether the Service is making improvement from more protracted issues that are less visible, and are not highlighted due to issues such as challenging data analysis, limited audit, under-reporting, misreporting, poor OA process awareness etc. As such, there may potentially be a bias to identifying improvement from high-impact, acute-risk issues as opposed to those that are of a more protracted nature.

Area for Consideration 16

The Service should consider reviewing whether there is a bias in the OA process towards predominantly developing improvements from high-profile, acute-risk issues that are more visible and easily identifiable.

Communication and Engagement

175. When asking staff about OA and outcomes, very few could articulate how effective it was and had no clear reference for its performance. This was compounded by the KPI measuring issue previously detailed and the lack of any visible dashboard or register of issues tool where input, outputs and outcomes could be easily linked and communicated. This issue was exacerbated by the large nature of input from operational staff and the OADs limited capacity to administer it and feedback directly to staff.

176. In addition, there would appear to be no process for ‘celebrating success’, where the links to change from staff feedback could be easily illustrated. As such, most staff found it difficult to ‘join the dots’ from their incident attendance feedback to actual improvement in the Service. Many of those we interviewed were left frustrated by the inability of the organisation to ‘close the loop’. An SA strategic priority action was, to develop feedback arrangements to inform staff involved in changes following lesson learned and to develop business partner engagement feedback processes. We have found no evidence to support that these actions are complete, and that tangible arrangement for change are in place.

Recommendation 8

We recommend that the Service develop a system to easily demonstrate the link between inputs, outputs and ORL outcomes to help maintain staff engagement.

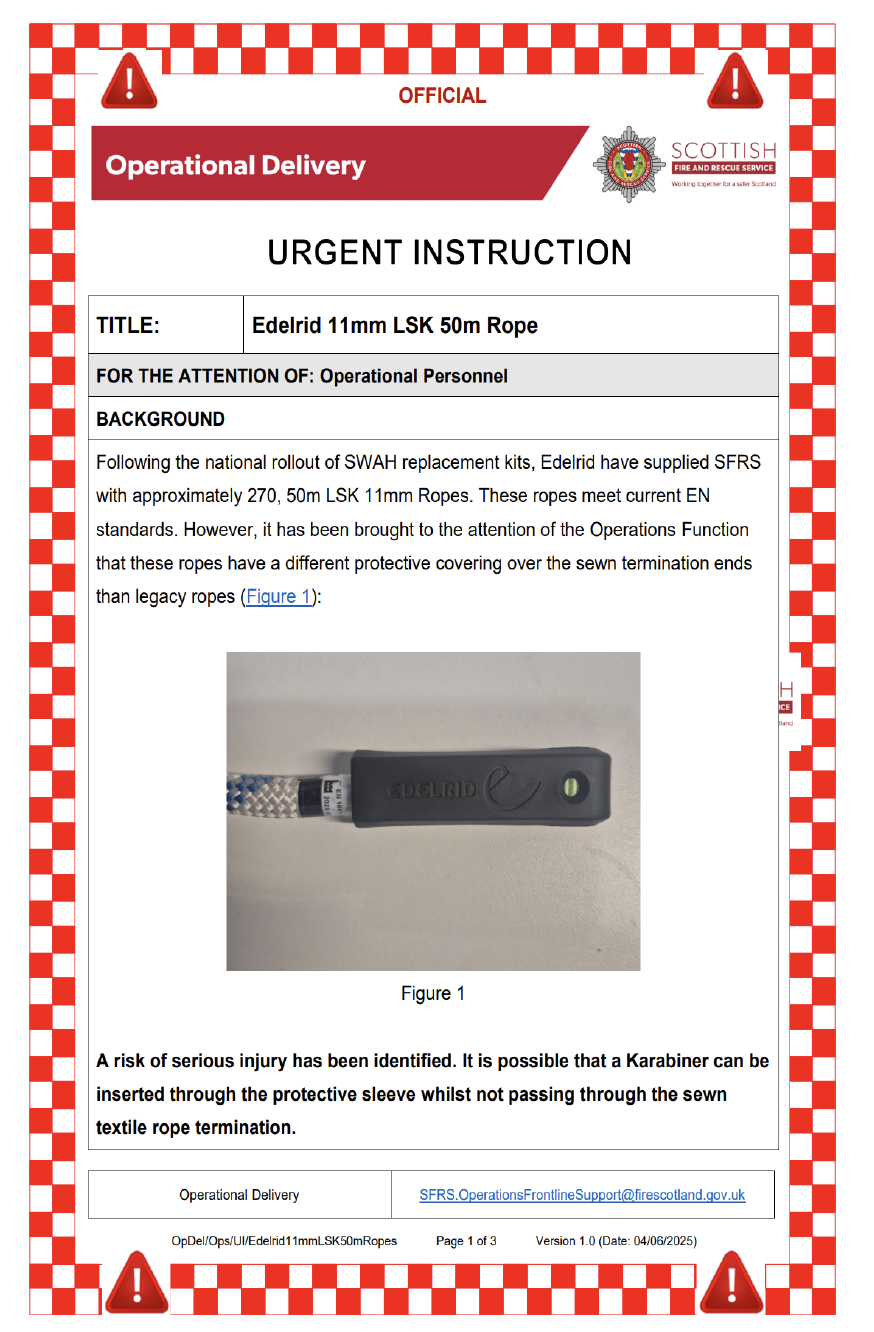

177. There are several communications documents the Service uses that are the embodiment of OA process and ORL output. These include UI, AB, FLU and CS. As the name suggests UIs (Figure 7) are designed to inform staff of an urgent operational issue and to provide remedial instruction. ABs are used similarly but for issues that are deemed to be of a less urgent nature. Both are issued in PDF format by email to all staff, are available on the OA intranet page and form part of a gateway process within Personal Development Recording (PDR) system, where understanding and awareness must be agreed whilst logging on.

Figure 7 - Urgent Instruction

178. Staff were generally positive in regard to these documents and felt that they helped improve safety. Support functions also found them helpful for supporting and communicating issues. Criticisms were, that sometimes far too many are published, which led to a degree of audience desensitisation. Sending UIs by email did not seem to fit the nature of the risk, particularly for on-call staff who find receipt of emails out with the workplace challenging and can therefore struggle to respond in a timeous manner. Other criticisms focussed on the lack of retraction of the instruction or brief from the primary document and that there did not appear to be a formal sign off process of UIs actions being completed. This issue was highlighted within a couple of LSO areas, where management of actions and accountability had been problematic.

179. FLUs (Figure 8) are used more as a learning tool and are developed with a specific theme that has been identified internally or externally from NOL. These are issued in PDF format by email to all staff and are available on the OA intranet page. We found a lot of examples of this tool being used to communicate information and learning to operational staff. Some criticisms centre on the fact that they could be too generic with lack of specific incident detail making them too sanitised. However, feedback from staff regarding these documents was overwhelmingly positive with many reporting that there was not enough of them (4 issued in 2023/24) and that they would welcome more.

Figure 8 - Frontline Update

180. These methods of communication are, to a lesser or greater degree, effective. Those that are consigned solely to learning are far more popular as they are viewed by staff as a development tool and can therefore help them to improve effectiveness and safety. We found many examples of these documents being used for staff briefing and prominently displayed within the workplace (Image 1), which is reflective of a positive safety culture.

Image 1 - Dumbarton Fire Station Notice Board

181. CS tend to be focussed on a particular high-profile incident and detail the learning from that incident, which is based upon the structured debrief process. They are developed in a video modular format, which allows for a much more interactive experience for the user with videos, diagrams and schematics forming part of the tool. The document is available on the OA intranet page and also forms part of the TFoC/PDR system. We found two examples of this tool being used to communicate information and learning to operational staff, George IV Bridge (Figure 9) in City of Edinburgh (CoE) and Albert Drive in CoG. Feedback from staff regarding these documents was overwhelmingly positive with many staff reporting that there was not enough of them and that they wished there were more. The only criticism of this tool was the time taken to publish the learning, for example, the CoE incident happening in the Summer 2022 with the CS being published Autumn 2024, over two years later.

Figure 9 - Case Study of George IV Bridge

Good Practice 9

The development of CS is considered good practice and is supported by most staff. This practice supports the ORL and LO concepts.

Culture

182. According to the Cambridge dictionary(33) culture is ‘the attitudes, behaviour, opinions, etc. of a particular group of people’ and is commonly described in an organisation as the way we do things about here. As such, it is difficult to provide quantitative evidence in relation to this section with heavier reliance on qualitative evidence. There was comment regarding the concern that OA is still viewed as a punitive process in some workplaces and that the Service had not quite achieved a culture where staff are entirely comfortable or open to constructive criticism. However, our overriding impression during this inspection was that the OA culture within the Service is relatively healthy with most staff believing in the ethos, understanding the need for the process, and eager to identify improvement opportunities. That said, there are a number of themes that we repeatedly observed that may highlight where the culture could be improved.

183. We were provided examples of the Service’s operational preparedness and response, specifically with regard to IC and staff decision making, which in some instances potentially contributed to accidents or near misses occurring. Staff appeared frustrated by this situation and could not fully articulate why they felt the Service seemed unable to preserve previous critical learning within systems and process. One person told us that previous learning should ‘be tattooed into the DNA’ of the organisation but could not explain why it sometimes struggled to do so.

184. Some of those interviewed pointed to the high turnover rate of staff in the last few years as a probable reason for challenges in preserving learning. However, we noted previously the NFCC state(34) that OL ‘involves the organisation embedding changes so that, even if there are staffing changes, measures to prevent reoccurrence stay in place’ and as such, there is an expectation that learning should endure within process, beyond the current muscle memory of its staff. Other staff detailed concern about the lack of focus on the operational mission and lack of engagement with end users in management decision making. This was underlined by the frequently reported perception of the Service routinely passing off genuine frustrations of staff regarding operational effective and efficiency as ‘moans’.

185. It is understood that learning from significant incidents should be embedded into the everyday business of the Service. However, by doing this there is the potential that the significance and importance of the learning may diminish over what can be a short or longer period as it becomes more routine. As such, there is always the risk that similar issues will repeat with similar consequences. There is therefore a need for the Service to consider how it maintains long-term focus on previous ORL in its decision-making processes. SA strategic priority actions were, to develop an OA campaign to embed and enhance the outcomes of robust OA on the incident ground and the development of a lessons learned programme for OL. We have found no evidence to assure us that these actions are complete, and that tangible arrangement are in place.

Recommendation 9

We recommend that the Service develop a system to record change, or significant ORL, which can be referenced and utilised for long-term strategic management and decision making.

186. Whilst speaking to staff about the OA we became aware that many managers would do the minimum administration required to satisfy the requirements of the process and then move it on. Some were not wholly bought in to the process and it became apparent that OA was viewed as a sacrificial piece of work in comparison to other competing priorities. There could be many reasons for the prevalence of this attitude but there was definitely a sense that OA was a function of command, and that the administrative process after any incident was more of an encumbrance than a real opportunity to improve operational performance.

187. There also appeared to be an urgency from some managers to discard the incident-related workload to get back to the priorities within their management role. Some staff felt that the Service was trying to do too much and inevitably there was not enough focus on things like OA. As such, this aspect of the culture would seem to favour focus on the completion of management tasks over operational improvement, which appears at odds with the value of safety and the Service’s overall mission.

188. OA involves most functions of the Service and encompasses both the levels of command and structure of management. Managerial roles and responsibilities are clearly defined in the OA Policy and supporting documents. The directorates of TSA and Operations have the responsibility for the assurance and delivery of operations, respectively. The command groups have the responsibility for incident command as well as operational preparedness and response. Specifically, the OAD has a clear remit of acting as the conduit and administration for OA information, but reaction can be limited due to challenges with analysis.

189. We found that OAD has no overt remit for policing standards. OA processes and governance is structured to manage significant incident trends, whereas command groups are very reactive and implement current procedures as opposed to having a strong learning remit. Whilst the OAO is a function of incident command and it is limited in its application as per our feedback detailed previously. Additionally, we also experienced the obtuse situation where LSOs who are responsible operationally and managerially for the performance of their area may not to be included in, or aware of, the wider OA processes initiated for that area, particularly if they were not part of the attending incident command team. We found this aspect of the OA culture confusing as it is unclear who has the responsibility for monitoring and reporting on flawed operational standards on a routine basis as well as learning and reporting quickly. As such, we observed the learning culture to be very bureaucratic, cumbersome and slow with potential gaps.

190. We interviewed staff throughout the Service area and became aware of a prevalent culture in remote rural communities. Whilst discussing operational issues we found many instances where there were challenges in delivering the standards expected in policy, operational guidance and procedures. It is understood that many of these documents were historically developed for consistency and continuity whilst the Service was completing the amalgamation process. The challenges cited, normally resulted in the restriction of incident support and attendance of additional resources.

191. Staff in these areas freely accepted these challenges and routinely fed back that they would normally just ‘make do and mend’ as the perception was that nothing would change. There was limited evidence that these staff ever formally raised concerns regarding the problematic application of policy and the consequential risk to their community and the organisation. There was an acceptance that many of the standards applied better to urban or less remote areas and could never be achieved locally in the current format or set up. Whilst commendable, it was disappointing to observe this resignation regarding the desire to urge for improvement via the OA system as well as development of policy that is fit for purpose and related to geographical restrictions.

192. We found that whilst there was an issue with under-reporting, linked to the previous section, the problem seemed to be greater than just that of a geographic nature. A culture of under-reporting also seemed to stem from issues such as lack of awareness of the OA process, reluctance to evaluate colleagues to a standard, limited knowledge of operational standards, ongoing perception of being a punitive process, disengagement due to lack of feedback and tangible outcomes as well as conflicting capacity and work priorities etc.

193. In addition, there was also an element of misreporting where staff routinely had confidence that because they had raised an issue with a line manager then it would be dealt with. This process normally resulted in disappointment as the line management process often failed to provide the result expected, particularly if the issue was of a regional or Service-wide nature. Thankfully, we found examples of line managers urging staff to formalise their issue within the OA system, which was pleasing to hear. However, there is still concern that this is not consistent across the Service and that many issues are under or misreported. This may be creating a culture of disengagement with the OA process with the possible loss of valuable learning for the organisation.

Area for Consideration 17

The overall culture towards OA was positive but the Service should consider these specific cultural issues in any review and further development of OA.